What if you could have a tiny text editor with different modes to emulate your choice of Emacs, Vi, Pico, NEdit, and even WordStar? Amazingly, such an editor already exists, and it’s called e3. It has no library dependencies, and its binary is less than 20KB.

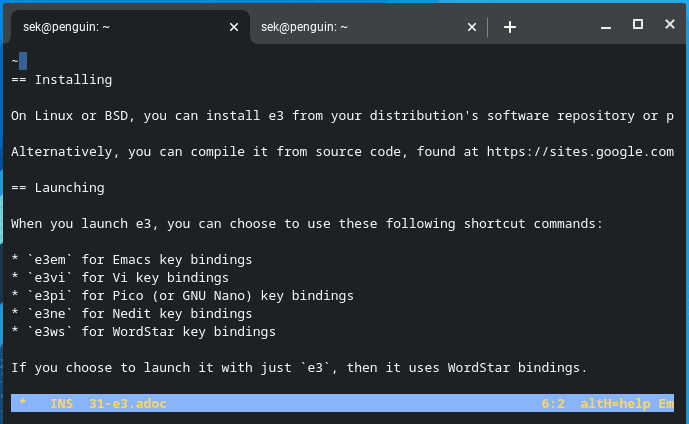

Installing

On Linux or BSD, you can install e3 from your distribution’s software repository or ports tree.

Alternatively, you can compile it from source code, found here.

Launching

When you launch e3, you can choose to use the following shortcut commands:

e3emfor Emacs key bindingse3vifor Vi key bindingse3pifor Pico (or GNU Nano) key bindingse3nefor NEdit key bindingse3wsfor WordStar key bindings

If you choose to launch it with just e3, then it uses WordStar bindings.

Using e3

As you might expect, the experience of using e3 is entirely dependent on which "version" of e3 you run. I’m not familiar with WordStar or NEdit, but the other defaults for e3 share one thing in common: e3 is not a replacement for your favorite editor.

There are hundreds of functions in GNU Emacs, for instance, that e3em lacks. The e3 editor provides you with the most common functions of your favorite editor, assigned to familiar keys. You can operate it on muscle memory for the tasks you perform most often.

When you launch e3, you’re placed into a buffer (a screen) containing a helpful list of commands. You can use the relevant keyboard shortcuts to open a file into the buffer. Alternatively, you can press Return to exit the help screen and the application. This is a little counterintuitive, so you’ll probably start e3 along with the name of the file, existent or otherwise:

$ e3em example.txtIf you’re familiar with the editor being mimicked, then you’ll be at home from the start. You can use your most common keyboard shortcuts to edit text, and when in doubt, you can press Alt+H (that’s Esc+H in Vi) to reach the Help screen.

Try e3

The e3 editor is an excellent choice if you’re looking for a small binary that’s easy to compile. There are no external library dependencies, so it’s relatively portable, even in binary form. It’s an easy way to feel like you have 80% of the features you rely on in a binary you can compile and run nearly anywhere.

3 Comments